The Hidden Layer Where AI Capabilities Are Now Built

Buried in a recent Anthropic product update was a detail that deserves more attention than it got: the PowerPoint, Excel, and Word file creation in Claude was not trained via reinforcement learning. It was built entirely through prompting and tooling. Anthropic calls these “skills.”

This is not a minor implementation detail. It suggests that new AI capabilities no longer have to come from training at all.

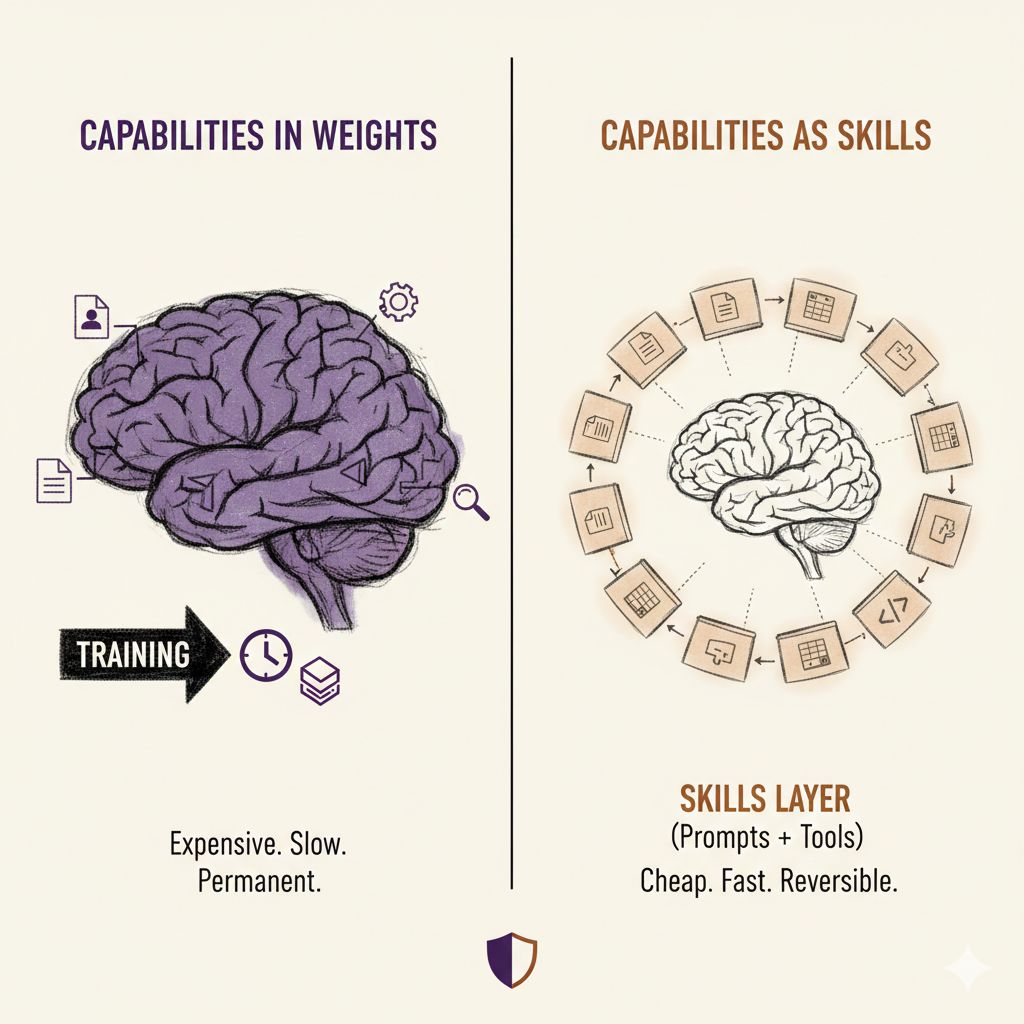

The Old Mental Model: Capabilities Live in the Weights

Traditionally, if you wanted a model to do something new, you collected data, designed rewards, ran RL, validated, and shipped. In this frame, product capability is downstream of training. The weights are where behavior lives.

This made sense when models were mostly standalone artifacts.

The New Reality: Capabilities Are Increasingly Built Outside the Model

Claude did not learn how to generate PowerPoint files because that behavior was reinforced into the weights. It learned it because engineers taught it how to use tools it already understood: Python, containers, file writers, and libraries like python-pptx.

In other words, the model already had the ability. The missing piece was orchestration.

A “skill” is not new intelligence. It is a structured way of directing existing intelligence toward a concrete, repeatable outcome.

This creates a second site of capability production: not in training, but in the layer around the model.

A Capability Supply Chain

Once you look at it this way, a pattern emerges:

- The base model provides general reasoning and tool awareness

- Skills translate that generality into specific, usable behaviors

- Only some of those behaviors eventually get compiled into weights

Skills are not just features. They are prototypes of capabilities.

They let teams ship a behavior, observe how it is used, see where it fails, and refine what “good” even means, all without touching training. That reverses the traditional order. Validation now comes before training, not after.

In this frame, reinforcement learning is no longer how a capability is discovered, but how a proven one is absorbed into the model.

Why This Matters Economically

Training is a large, irreversible, and slow investment. Once behavior is baked into weights, it is hard to undo, expensive to change, and risky to generalize.

Skills are the opposite. They are incremental, local, and reversible. You can ship them quickly, modify them cheaply, and remove them without collateral damage.

That changes the economics of capability development.

Not every useful behavior should justify a training run. Some capabilities are high-frequency and foundational enough to deserve being internalized. Many are not. They are better left in the orchestration layer indefinitely.

This mirrors the shift from compile-time to runtime in software: not everything has to be decided when the program is built. Many behaviors are defined dynamically, at execution time.

AI systems are undergoing a similar shift, from compile-time (training) to runtime (skills and orchestration).

The Deeper Implication

This blurs a line that used to feel clean: the line between “the model” and “the product.”

Some capabilities live in weights. Others live in prompts, tools, and orchestration. The boundary between them is not architectural. It is economic and operational.

If you are building AI infrastructure, this has a clear implication: the prompt and skill layer is not glue code you will eventually compile away. It is a first-class capability surface.

And increasingly, it is where product differentiation happens.

Inspired by an Anthropic product update discussing how skills enabled rapid capability iteration independent of training cycles.